An Endless Torrent

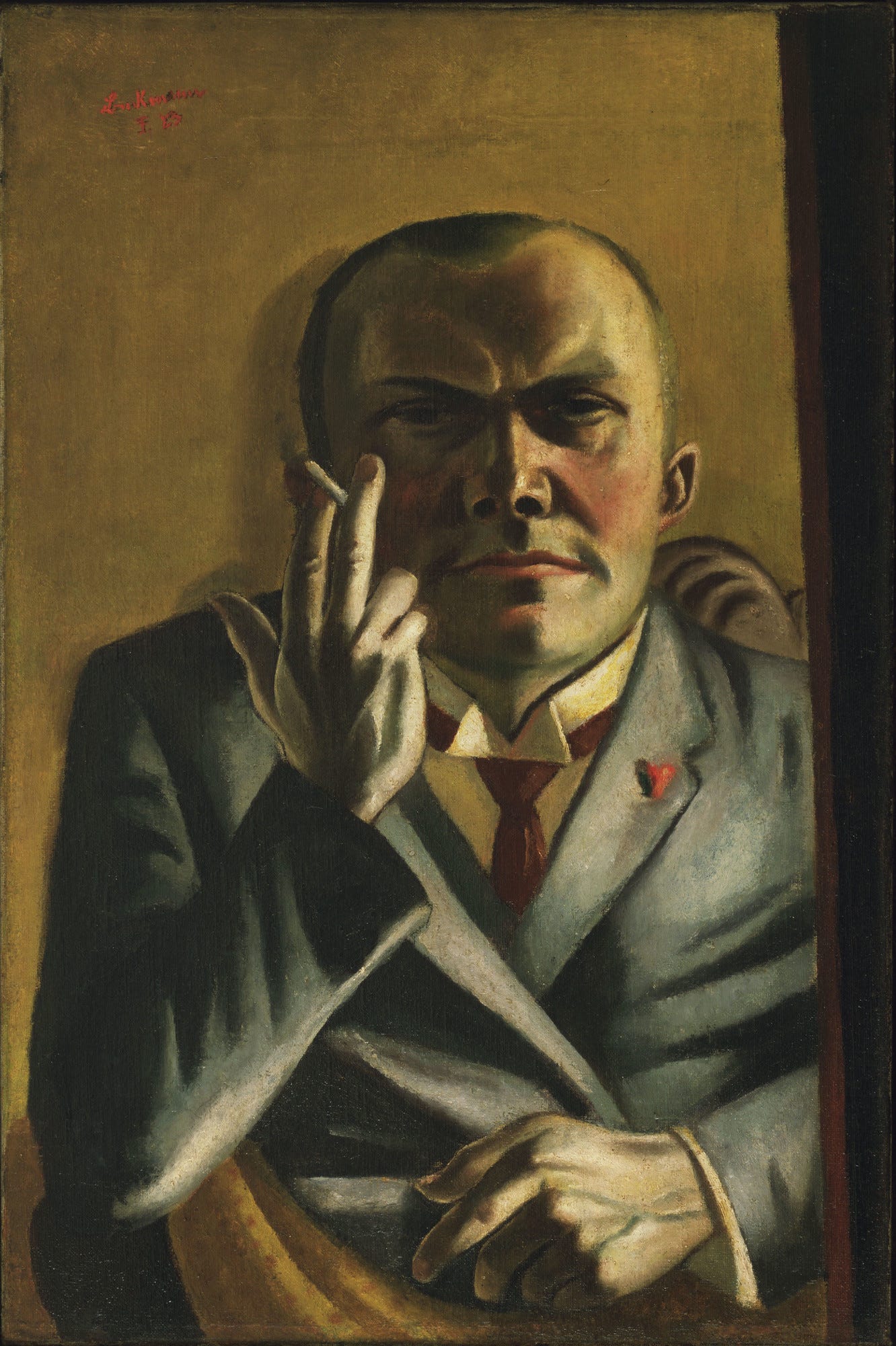

The Great Disorder: Politics, Economics, and Society in the German Inflation 1914-1924, Gerald D. Feldman, 1998.

This is the second part of my review of Feldman’s magnum opus on the Weimar hyperinflation, The Great Disorder. If you have not already, I would recommend reading part one first.

When we think about the Weimar hyperinflation, it is difficult not to become mesmerised by the shock and awe of 1923. It is the one-hundred-trillon mark banknote issue. The political, theoretical, and economic tensions I considered previously can seem minor against this catastrophic year. The dislocations of late 1922, severe in their own right, appear as little more than a prelude. Prior to the war, the exchange rate was roughly four marks to the dollar. In 1922, it reached 1500 marks to the dollar. This was a substantial fall, the culmination of a long process that reached back into the early years of the war. But by the end of 1923 - the peak of the hyperinflation - 4,200,000,000,000 marks went for one US dollar. Four trillion and two-hundred billion. The clichéd vignette is a housewife pushing a wheelbarrow of cash in order to buy a loaf of bread. That this is the dominating memory of the inflation, and even of the Weimar Republic itself, is understandable.

However, there is a reason that Gerald Feldman, writing a book to anatomise and diagnose the great disorder which hyperinflation represented, is mostly concerned with developments before 1923. A sharp discontinuity can hide the persistence of continuities. In this case, as Feldman writes, “the crisis year of 1923 recapitulated in exaggerated and often grotesque form the entire range of decisions and conditions that had propelled the inflation since 1914”. In the second book of The Great Disorder, Feldman suggests looking beyond just the numbers on the banknote and placing the hyperinflation - in all its economic, political, and social manifestations - in proper context.

The immediate trigger to the hyperinflation was the French occupation of the Ruhr in January 1923. In response, the government of Wilhelm Cuno adopted “passive resistance”. The Reich paid workers in the Ruhr not to work, so as to stymie French plans to seize coal and customs revenue. While popular - the colourful industrialist Hugo Stinnes declared a willingness to dynamite his own coking plants - the policy was not effective, sustainable, or affordable. Passive resistance threw a grenade into the already parlous finances of the Reich. Deficit spending exploded. This placed extreme pressure on the value of the mark. While the Reichsbank defended it successfully for a few months, by August this was no longer possible. A descent towards worthlessness was the result. By November, the mark had ceased to function as money, except where the laws mandating its use were enforceable, such as in retail. Wives waited at the factory gates so that they could spend their husband’s payslip as quickly as possible. This is the hyperinflation we are familiar with.

The necessary context crudely established, what can Feldman teach us about the hyperinflation? As I mentioned, the exaggeration of existing tendencies is drawn out keenly by Feldman. The mythical humiliation of the Mittelstand, so central to narratives about the collapse of the Weimar republic and Nazism, is an example of where this shines through. Despite the myth, the ‘middle class’ of Germany did not evaporate. Small retailers and petty landlords suffered, as did anyone holding an unfortunate quantity of war-bonds, but those holding small industrial portfolios or a mortgage did quite well. The trauma this class experienced, which ultimately untethered it from republicanism, was a result of two causes: an internal disunity exacerbated by inflation, and the sense of falling behind the better organised industrial working-class. I was particularly impressed here - this argument is frequently waved by with generalities, but Feldman goes in for every detail: the hand-wringing in the legal system over the principle of ‘mark for mark’ (that a prewar mark was worth as much as a postwar one), an inflation-sparked reckoning within the insurance industry, the tensions inside the professoriate, and the protections afforded to civil servants that aroused so much intra-class jealousy. All contributed to a fracturing of Germany’s vaunted centre-right coalition. All were also issues which did not emerge in 1923, but had been gestating since at least 1919. The hyperinflation simply exaggerated them to extreme, unbearable proportions.

Another strain of intensified continuity concerns the business atmosphere of the hyperinflation. It is worth remembering that the inflation before 1923 had been experienced as a boom. Industry benefited from decreasing real wages as the mark devalued. This is how inflation let Germany buy time in resolving its internal tensions. Boom conditions, with a sprinkling of monetary illusion, kept industry and labour contented. Further, foreign speculation on the mark by those betting on a recovery had also given Germany an interest-free loan. But all of this had come at a cost. Feldman cites Keynes, who argued in 1922 that “in the modern world, organisation is worth more in the long run than material resources”. The inflation had concealed declining productivity. The hyperinflation exposed it. With transaction costs exploding, German export industries found themselves unable to compete even as the mark plummeted further. The vital capacity of inflation to massage social conflict was lost.

I think this is a fitting point to bring in Charles Maier’s Recasting Bourgeois Europe. Although Feldman is writing in Maier’s shadow, there is little direct engagement with his book or its ideas in The Great Disorder. Still, Feldman does have an implicit commentary on Maier, I thought. Corporatism, while invoked occasionally by Feldman, is used hesitatingly in the Great Disorder. While Maier’s corporatism is quasi-deterministic and trans-European, the image of industrial compromise Feldman paints is instead contingent and fragile; dependent upon inflation and the narrow political priorities of the Weimar state. In this sense, it is less comparable to the arrangements that came about in fascist Italy. To an extent, this difference is aesthetic. But it does indicate how each author conceptualises the interaction of inflation with political economy differently. For Maier, bourgeois stabilisation had momentum of its own. While in Italy, France, and Germany the politics of inflation manifested differently, in all cases it was downstream of the push towards retrenchment. For Feldman, this is reversed. The inflation not only facilitated a fragile stabilisation in Weimar Germany, it was the driving force behind it. Inflation was the glue holding Weimar corporatism together. This blunts comparisons with the much more firmly-founded Italian corporatism.

The last aspect of the hyperinflation to consider is perhaps the most obvious, but also, I believe, the most intriguing. Even at the depths of the inflation in October and November, the fear of how the hyperinflation would end was as much of a concern as the pain of it continuing. Somewhat counterintuitively, hyperinflation brought a severe liquidity crisis. For those firms which could not avoid using marks (such as retailers), there was never enough cash to go around. Firms, even those doing great business, struggled to meet their daily costs. The difference in prices from one day to the next consumed all takings. Operating capital was brought to an absolute minimum. A voracious demand for credit such as this could only be maintained with the printers running full steam - when, in once instance, the printers went on strike, a massive crunch was only narrowly avoided. The government, the value of whose tax receipts had been wiped out, also became trapped by a similar dynamic. Of course, all parties would prefer a return to a stable currency that functioned adequately as a store of value and a means of exchange. But getting there was a terrifying proposition. The many debates over valorisation of prices and wages - linking to gold directly even if denominating in marks - illustrate this. Could avoiding an abandonment/revaluation of the mark, while staying ahead of inflation, be systematised sustainably? Was a climbdown possible without a fall? Feldman’s analysis reveals that for many industrialists, politicians, and union organisers, the only prospect worse than further devaluation was revaluation.

The Great Disorder really is an immense achievement. Even across two fairly wide-ranging posts, I have only given a crude splattering of the themes that Feldman charts in exquisite - if sometimes inelegant - detail. I have also left out the stabilisation process, the focus of Feldman’s final chapters (I plan on redeeming this in my next post on Adam Tooze’s The Deluge). But the book is not without weaknesses. Feldman’s laser focus on Germany is powerful. As I mentioned, it allows pouring some cold water on Maier’s corporatism thesis. However, it also meant that - despite the book’s length - I felt that essential issues were under-explored. Maier’s account of the Franco-German to and fro during the Ruhr crisis is far superior to Feldman’s. Further, the financial story is impeded by the strictly national focus. British and American actors feature as interlocutors to their German counterparts on occasion, but are not treated as important puzzle pieces in their own right. All said and done, Feldman could have spent less time block-quoting Stinnes’ ultimately vain pontifications and more fleshing out the international dimension with the requisite gravity. Still, this might be asking for a different book. The fact is that The Great Disorder is, to the best of my knowledge, without substitute. Inelegant? At times. Analytically ambitious? Not really. But is there another no-stone-left-unturned analysis of the Weimar inflation - and the political economy of inflation more broadly - that comes close in terms of ambition, execution, and sheer meticulousness? I do not believe there is.