The Great (Fiscal) Divergence

State, Economy and the Great Divergence: Great Britain and China, 1680s -1850s, Peer Vries, 2015.

Often, I can feel compelled by a book with likely unsound arguments simply because it is well-written, charismatic, or particularly tight. If you’ve ever read older texts, you are probably familiar with this feeling. But with Peer Vries’s State, Economy, and the Great Divergence I found myself in the opposite situation; convinced by the argument despite much of the experience reading it.

The main thrust of the book is classic counter-revisionism: Vries argues that while the nineteenth-century perception of Qing China as “vegetating in the teeth of time” has been rightly overturned, the pendulum has swung too far*. Historians, especially those of the so-called California School, who argue Qing China was, by the end of the eighteenth century, as developed as Britain are kidding themselves. This is most true concerning Vries’s main focus: the state. The Qing state was substantially weaker than her European counterparts, especially Britain. As such, China was left behind in the mercantilist competition of the eighteenth century; where success, Vries argues, was a precondition of capitalist development.

Although not ‘optimal’ in the same way free trade and unimpeded markets are, within the ruthless environment of the early-modern world, to the most powerful state went the spoils. Rather than simply stepping back and providing benign institutions, Vries argues the successful early-modern state had to maintain a bureaucracy capable of taxing effectively, and support a military capable of winning wars. The Qing state oversaw a relatively well-functioning market economy with minimal interference - what has been described as “agrarian paternalism”. But without the state ‘infrastructure’ needed to support a competitive bureaucracy, army, and navy, China was unable (if also often unwilling) to protect and further its economic interests.

The underdevelopment of the Qing state rested on two, interconnected pillars: low revenues and low, inflexible expenditures. Despite the charge of ‘oriental despotism’ once levelled against it, the Qing received relatively little tax income. Per capita, Vries estimates the British government received, circa 1800, eighteen times as much tax revenue as the Qing. This is not just because British subjects were wealthier - the ratio of tax income to national income was still (very roughly) twice as high in Britain as it was in China across the eighteenth century. Even by 1911, Qing tax income only amounted to 2-3 percent of net national product. Part of this was due to low nominal taxes, but an even larger part of can be explained by inefficiencies in collection. Most revenue was retained - legally or illegally - by provincial authorities. In a share that would only decrease over the nineteenth century, only 25% of revenues made it to the Qing treasury. Withheld taxes would at best support under-resourced local administrations, and at worst were seized by corrupt magistrates. Of course, due to the size and population of China, these difficulties may have been unavoidable, as Vries acknowledges. But that does not make them any less real.

The above numbers give some indication of the difficulties of the Qing state by themselves; after all, it is hard to imagine any state apparatus functioning smoothly on such low income. But observations from the expenditure side further reveal the situation. Local officials, soldiers and bureaucrats were insufficiently paid, and few in number. This did nothing to alloy tax collection issues - underpaid and overburdened bureaucrats, expected to pay state expenses themselves, frequently resorted to ‘extra-legal’ methods in order to raise revenues. Moreover, the total number of government employees was shockingly low. Although admitted through prestigious examinations, the Qing employed few bureaucrats: boasting less than 30,000 central government officials in 1850 - 0.007 percent of the total population. By comparison, 0.24 percent of the British population was employed by the state in 1850, rising to 0.42 percent by 1880. Clearly, the Qing were stuck in a low-revenue/low-expenditure trap, with little political impetus - or capability - to escape it.

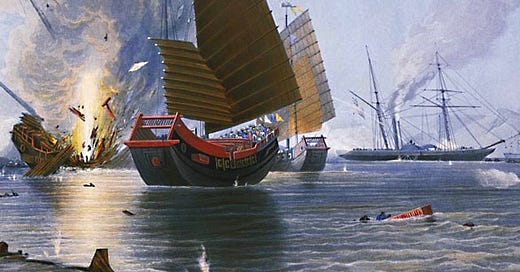

Compounding these deficiencies was the inability and unwillingness of Qing China to engage in over-expenditure. For Western Europe, the constant demands of war often necessitated expenditures above income; in other words, finance. As such, a sophisticated service sector emerged to provide exactly that - yet again, most prominently in Britain. Without the same competitive pressures, China had never developed such a system. Until the 1850’s, the Qing had never taken on public debt. By comparison, British national debt was never lower than 100 percent of GNP from 1760-1860. Resultantly, the Qing state never developed the ability to effectively manage debts. It would buckle to near-collapse under the strain imposed by the debts the Opium Wars imposed - debts much smaller than Britain carried after Waterloo, or France after Sedan.

Of course, a ‘big government’ has no direct bearing on economic growth. The same goes for the extent to which the state can borrow cheaply. If anything, both are often seen as antithetical to it. For Vries, however, this ‘infrastructure’ was vital for early modern economic development; in large part because, as mentioned earlier, it gave the state tools to fend off competitors. Vries estimates Britain spent more than ten times per capita on the military than China did from 1760-1820. Half of this expenditure went to the navy, to which Britain devoted more resources than any other state. Apart from supporting industrialisation in itself (the dry-docks of the Royal Navy were early adopters of steam engines), naval supremacy allowed Britain to conduct international trade on its own terms. In turn, this allowed it to capture the majority of gains trade created; exerting monopoly power on transport, distribution, insurance and protection. This strategy was exemplified in the trading practices of the British East India Company, and later, in the outcomes of the Seven-Year, Napoleonic and Opium Wars; for all ultimately see Britain forwarding her economic position through capitalising on her mercantile strength. China’s inability to do the same, Vries believes, greatly encumbered her prospects for modern economic growth.

I have not exhausted the arguments of State, Economy and the Great Divergence. Vries also considers monetary issues, tax choice, empire, and the ‘legibility’ of states; among other things. But I felt these fundamental fiscal differences to be the crux of his argument. When compared fiscally, the “surprising resemblances” between Britain and China à la Kenneth Pomeranz are least apparent. Although his presentation of evidence sometimes resembles a loosely stitched quilt - relying on what he himself describes as “very rough estimates” - Vries reveals remarkable differences and makes a plausible case for why they mattered. Although I think his case is slightly overstated, I wouldn’t have had many criticisms if the argument stopped there. The problem, however, is that it does not. Vries is also interested in criticising pretty much all alternative approaches to the state, to the detriment of his book as a whole. I think this is best illustrated by quoting extensively from his conclusion.

“…the state matters in ways that are not adequately dealt with by most economists, whether it is neoclassical economists who claim that it should only facilitate the market and get the prices right; neo-institutionalists like North, Wallis and Weingast or Acemoglu, Simon and Robinson who claim it should just take care of inclusive institutions; Keynesianists who primarily focus on expenditures, or neo-Marxists who like to treat the state as just a representative of certain societal classes.”

As that monster sentence makes evident, there was a whole book Vries could have written on this topic alone. But apart from brief treatment in the conclusion, these ideas crop up seemingly at random, in amongst the comparative, descriptive analyses of Britain and China. Usually, there is not much more than an acerbic remark on how Acemoglu has not done enough research. I won’t try and assess the critiques hinted at above; suffice to say, I think none are analysed in enough detail to facilitate an informed decision. If it is beyond Vries in a 450 page book, it is beyond me here. Given none of the arguments made in State, Ideology and the Great Divergence depend on these criticisms, I believe they should either had been treated elsewhere, or discussed within the appendix; regardless, they are done a disservice in the haphazard way they are delivered. It makes what would otherwise have been an argumentatively tight book feel much looser, which is a real shame.

Nonetheless, I think Vries does grasp an essential truth in State, Economy and the Great Divergence. The difference in state capacity between early-modern Britain and China was too great, and too deep rooted, to have been irrelevant to their economic development. However, Vries has not convinced me that “the First Industrial Revolution can be plausibly represented as a paradigm example of successful mercantilism”. If mercantilism did facilitate industrialisation, it did so inefficiently, and in all likelihood, largely accidentally. Having a powerful state may have prevented others from smothering British industrial growth in the cradle, but other factors (North, Allen, Mokyr, etc - take your pick!) actually made Industrial Revolution happen. If I was to reword Vries, it would be to say that the paradigm example of a successful mercantilism is not the First Industrial Revolution in Britain, but rather, it is the lack of a Chinese Industrial Revolution in the same period. Explaining this, I believe, is where the value of State, Economy and the Great Divergence lies.

*The quote is from Hegel. I wrote about this previously in the context of Perry Anderson’s Lineages of the Absolutist State. You can read that here.