Cracking Glass

Balance of Power: Central Banks and the Fate of Our Democracies, Éric Monnet, 2024.

Without a doubt, central banks — and central bankers — are among the main protagonists of our era. Bernanke, Draghi, Powell: these names will inevitably accompany all attempts to periodise the time from the financial crisis to our present moment. For the period before then, Volcker and Greenspan already do: the ‘Volcker shock’ is, in most accounts, still one of the main hinges of the late 20th century. This was not always the case — I would be suprised if many can name a prominent central banker from the 50s and 60s, and for a reason: the central banks of the postwar period were very different to what they have become today. Our central bankers operate under a different global monetary order. Their balance sheets are larger, their powers broader, and they pursue different goals. Most importantly, their legitimacy derives not only from their role as a ‘bank for banks’ and their responsibility as protector of the currency, but from the perception they act in the popular interest. But, after more than a decade of unconventional monetary policy, extravagance and austerity, and a return to higher interest rates, that perception has never looked so fragile.

Éric Monnet’s Balance of Power is a brilliantly concise book. On the one hand, it explains what central banks do in an accessible, sufficiently technical, and historically founded manner — a useful contribution in itself, given that most undergraduate macroeconomics textbooks declare that ‘central banks set the interest rate’, gesture vaguely at fractional reserve banking, and leave it there. But Balance of Power is not a textbook chapter. In fact, it is best described as a manifesto. Monnet is writing because he thinks central banks today have a democratic legitimacy deficit. He questions their capacity, under the current paradigm, to tackle the problems of the twenty-first century. He worries that left unchecked, central bankers may saw off the branch on which they sit: an increasingly fragile public perception that it is they, not elected governments, who should be responsible for managing the currency.

“Central banks are contradictions” — so Monnet opens the book. “They are agencies of states, but they are not domains of governments. They provide credit to financial institutions to advance the public good, but they have no role in determining what the the public good actually looks like”. Paradoxes are everywhere in Monnet’s eyes: the near “omniscient” position of central banks after 2008 is a product of how vaguely their powers were articulated beforehand, and it is because central banks became “too independent” that governments have “unloaded” so much responsibility on them. But Monnet’s solutions embrace this contradictory logic. He believes central banks can be made more independent and democratic, while their powers simultaneously restricted and expanded, to ensure they are fit to meet the challenges of this century. This is possible, Monnet argues, if we rethink how to institutionalise central bank independence.

Central bank independence is the most venerable idea in the political theory of monetary policy. Simply put, it is the idea that the institution which is in control of monetary policy should not be subjugated to the institution which makes fiscal policy; or, for that matter, any other branch of government, such as the executive. It is considered to be important for a number of reasons: so the long-term target of price stability is not sacrificed to short-term politics; so the central bank can be credible and time-consistent to maintain financial stability; and, in the broadest sense, so monetary policy is not perceived as in the interest of particular classes, sectors, and complexes. In the interwar era, this principle was considered sacrosanct: an attitude facilitated by the largely private central banks of the time, and the brutal realities of the futile effort to maintain the gold-exchange standard. In the postwar era, dissatisfaction with the performance of central banks during the Great Depression led to reform and nationalisation in many cases, and independence took a backseat to co-ordinated counter-cyclical monetary and fiscal policy. But with the expansion and liberalisation of finance from the 1980s until 2008, independence was re-established as a core principle. Since the financial crisis, it has facilitated the unprecedented actions of central banks. And crucially, it has led to a situation which, paradoxically, has left the “glass case of central bank independence in liberal democracies quietly cracking”.

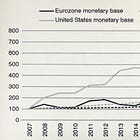

The problem with ‘really-existing’ central bank independence is fundamental: independence from whom? We have yet another paradox: that strengthening central bank independence before the decade of crisis is precisely what made it possible for central banks to buy public debt without constraint, and hence a situation where financial stability and the public debt are unprecedentedly co-dependent. Before the crises, central banks held on average 10% of public debt. By 2021, this had grown to between 30-50% (while Monnet misses that since 2022 this has been partially unwound, it is still nowhere near pre-2020 levels). Whether ‘normalisation’ of this situation is possible, or even desirable, remains unknown. This is precisely where central bank independence comes in. Central banks unwinding these positions risks triggering higher yields on bonds and destabilising the financial system. But not unwinding is fraught, as it involves acknowledging that the government’s interest in low interest rates is inextricable from financial stability, and “the definition of financial stability is in fact dependent on the mode in which the public debt… is financed”.

Monnet is not arguing, however, that any of this is inherently problematic for democracy. But with unconventional monetary policy cracking the glass case of independence, the entrenched opacity, partiality, and unaccountability of central banks is exposed. In another so-called paradox, Monnet observes that the legal framework of central banking has created “political entities — board members — whose interests and precise representative roles are impossible to characterise, let alone question”. This is as true of the ECB as the BoE, Fed, or RBA (although Monnet is most interested, naturally, in comparing the ECB and the Fed). Furthermore, there is very little expertise capable of criticising central banks outside of those banks themselves. Almost half of all articles on monetary policy, Monnet observes, are authored or co-authored by a central bank economist. Most importantly, parliamentary bodies are ill-equipped to provide accountability or check the transparency of their central banks.

So how can central bank independence become compatible with democracy?On the one hand, Monnet believes that central banks should be able to make decisions without instructions from the government — this is what separates his call for democratisation from that of Donald Trump, for whom the central bank would ideally be beholden to the whim of the executive. Rather, Monnet sees democracy as a “system of checks and balances, not the unlimited power of the parliamentary majority”. Hence, democratising central banking involves incorporating central banks into the balance of power between the spheres of governance; restraining their omnipotence and opacity by strengthening four key traits: reflexivity, accountability, impartiality, and transparency. My latent Jacobinism makes it hard to swallow this concept of democracy. Still, I accept that if central bank independence is the goal, this seems as good as it gets.

However, this is where Monnet seems to be more bark than bite. His solution, presented within the context of the ECB, is a European Credit Council. This is a hearkening back to the post-war period, when credit councils co-ordinated fiscal and monetary policy in many European states (as much as was possible under Bretton Woods, that is1 ). But Monnet’s Credit Council would be simply an advisory body. As he writes, “the credit council would not play a decision-making role. And the ECB would not answer to this council, but still to the parliament”. In general terms, it would be where “existing institutions are co-ordinated”. I do not disagree with Monnet: I am sure such a council is a wise idea. But it does not seem to match the scale of the crisis he identifies — the “fate of our democracies” and so on. I wish central bank independence could be made compatible with democracy through an advisory body. But I suspect — thanks to Monnet! — the problem is deeper. As Monnet shows, central bank independence is in crisis as much for systemic macroeconomic reasons — in the size and politics of balance sheets, and the credit policy of the ecological transition — as for reasons of the institutional balance of power.

Because of this, Balance of Power reminds me of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century (incidentally, Piketty describes Balance of Power as an “unflinching, revelatory book” in a blurb on the book’s cover). Both Piketty and Monnet look at a contemporary political issue (economic inequality and central bank independence) with a historical perspective informed, above all else, by postwar Europe. Both persuasively outline the stakes. But both finish their argument with solutions that do not meet the scale of the issue that the authors themselves have set up! (if you remember, Piketty finished Capital by calling for a global wealth tax — a deus ex machina if ever there was one). This does not negate the many insights in either author’s work: I believe Capital in the Twenty-First Century deserved its fame, and while I doubt that Balance of Power will match that, it would not be undeserved if it did. However, you are left wondering if both authors are more unsure than their manifestos let on.

Paid subscribers: check out the supplemental to this review below! If you are not yet a paying subscriber and you’re curious for more, please consider signing up.