Downstream

A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World, Gregory Clark, 2007.

I have not reviewed many grand histories of global economic development on this blog. This is largely because, embarrassingly, I have not read that many of them. Robert Allen’s Global Economic History, Mark Koyama and Jared Rubin’s How the World Became Rich, and this, Greg Clark’s A Farewell to Alms: all have somehow slipped through the cracks.

This is a mistake I should have rectified long ago. I am increasingly aware that this sort of work is extremely valuable, even for those who think that they are across the literature. It can be difficult to make out the pattern if you stare at single threads at a time.

Well, now I have a perfect opportunity to fix this. My coursework is giving me a reason to tackle important texts which I have so far left by the wayside (and also an incentive to align what I write about here with what I have to write on there!). Until a few weeks ago, I had planned to delve into the Brenner Debate after finishing with the mediaeval Mediterranean. With academic pressure in mind, I will be putting this on hold, temporarily. Instead, over the next couple of months I will look at (in a completely arbitrary order!) a series of canonical texts: first Clark, then Joel Mokyr, and, maybe, Douglass North. A relief I hope for those of you sick of mediaeval peasants and Jewish-Egyptian merchants.

A Farewell to Alms is interesting because, perhaps unlike its stablemates, it is not so much a book about how the world became rich, but about why it took so long to happen. Clark devotes many more pages to his model of why long-run growth persistently escaped humanity, than to why we eventually found it. This maybe reflects Clark’s two, rather unfashionable, idiosyncratic views: a commitment to a Malthusian framing of the pre-modern world, and a story about the emergence of sustained growth which emphasises not institutions or geography, but the culmination of a Darwinian process of selection.

If you are not already familiar with Clark, I imagine that final part raised some eyebrows. But before I get to that we should deal with Malthus. Clark believes that the so-called ‘Iron Law of Malthus’ ruled humanity until about 1800. This is a simple model based on the assumption of two factors of production, land and labour, where land is fixed and thus labour faces diminishing returns. Its main result is even simpler: that income per capita in a Malthusian world was determined purely by birth and death rates. Technology may lead to a short-run improvement in incomes, but this would cause population growth which, in time, would whittle it back down — the only ultimate ultimate effect being an increase in population. Echoing Marshall Sahlins, Clarks argues this model reveals how our Palaeolithic ancestors despite inferior technology were likely better off than their eighteenth century counterparts.

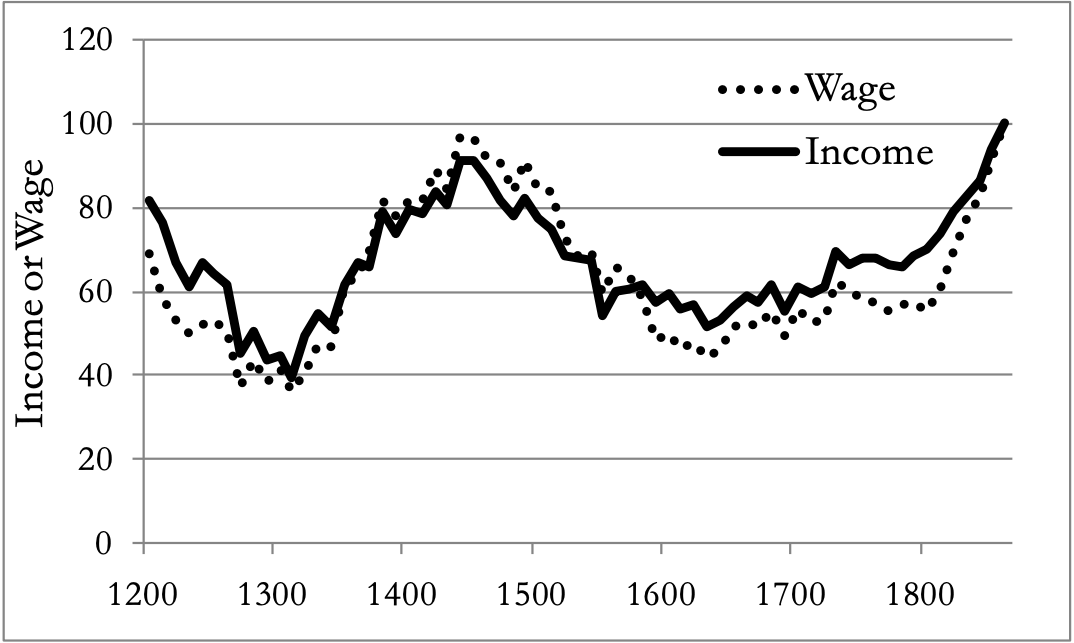

The keystone piece of evidence Clark deploys to prove this is his English real wage series, which basically has a stationary trend until about 1800 — that is, there is no significant improvement in wages from the dawn of history up to the Industrial Revolution. While I generally try to avoid putting any charts in these reviews, I feel I must make an exception here.

This chart does seem fairly definitive: if it is accurate, and if wages are a solid (and consistent) proxy for living standards over the long-run, Clark is justified in describing all pre-modern history as Malthusian. But these assumptions, in 2007, were controversial. Today they are probably even more so. The work on long-run GDP in the last decade (most notably by Stephen Broadberry) paints a different picture to Clark. There we have a greater emphasis on a gradual increase of living standards from about 1200 on, precisely not the volatile-if-stationary trend the Malthusian model predicts.

It is also not obvious that wages themselves are settled. Clark’s series is based on English agricultural day wages. In some ways, wages are much less opaque than famously Byzantine historical GDP estimates. But they have many issues of their own. Understanding how wages in a particular sector, region, or time mapped to average incomes requires a level of detailed knowledge we usually do not have. Robert Allen’s (in)famous construction wages look different from Clark’s, and both potentially suffer from failing to account for changes in how many days were worked in the year.1

Perhaps the counterintuitive but alluring idea that early-modern people, with their ploughs, potatoes, windmills and gunboats, were no better, or worse, off than cavemen is counterintuitive because it is wrong. Maybe recent empirical work has busted that well-worn observation than ‘Malthus was right about all of human history up until his own era’, because he wasn’t. But, perhaps not. In a recent (2022) discussion paper, Clark claims that, if one takes into account a spate of different metrics, he was right all along.2 I still do not think that I am fully convinced. But I have to acknowledge that Clark could, at least, be right.

This debate over the Malthusian model is as old as economic history — maybe even economics — itself. But it is not necessarily obvious how it is relevant to any theory of why long-run economic growth emerged. For most big theories of historical economic development, emphasising, technology, institutions, or geographic endowments, demography is downstream. But in Clark’s view, this could not be more wrong. Clark rejects all conventional theories in A Farewell to Alms. Everything, from incentives to politics to science, is irrelevant as far as the Industrial Revolution is concerned. Instead as Clark memorably puts it, “Britain’s rise to world dominance was a product more of the bedroom labors of British workers than of their factory toil”.

That colourful remark actually pertains to Clark’s lesser-known argument for why the industrial revolution happened specifically in England. A mysterious but unambiguous explosion of the English population in the early eighteenth century, he argues, caused industrialisation simply by raising the demand for food beyond what England’s fields could sustain, creating a need for imports and, mechanistically, the export of manufactures to pay for them. This strikes me as a strange position. Having exerted much effort arguing that improving incentives for inventors were not causal for industrialisation, Clark seems to turn around and suggest that the sheer logic of the balance of payments was somehow enough, without much in the way of explanation about how such a mechanism would actually work. Perhaps I have misunderstood his point, but still — on the surface, at least, Clark’s seems a rather weak answer to the ‘why Britain’ question.

But putting that specific point aside, “bedroom labors” genuinely are the crux of Clark’s theory of historical economic development. In his Malthusian world poor people died young and childless while the rich went and multiplied. The traits of the successful — patience, rationality, and intelligence — were passed on, while violent and impatient genes died out. Eventually, a tipping point was reached, where technological development reached a rate sufficient to break from the Malthusian chains. Economic development occurred because people became better at it, and the Great Divergence because Europeans did so first.

For so many reasons, this is a view I struggle to get behind. I doubt that many would: there are not too many subscribers, I believe, to this Darwinian theory of economic development. But my impression is that the consensus is moving towards Clark’s perspective, if in a somewhat underhanded way. The idea that something pervasive and with deep, long-run roots caused the divergences in economic growth has increasing support. It is the essence of the ‘institutions as total social equilibrium’ school of thought espoused by Tabellini and Greif, even if in that context, cultural path-dependence, not biology, is understood to be the prime mover.

The resemblance between the two perspectives is actually even closer. I was glib when I characterised Clark’s Darwinian view above — he does emphasise culture, even if his ‘theory of change’ is demographic/biological. Clark argues that “the development of cultural forms — in terms of work inputs, time preference, and family formation — [is what] facilitated modern economic growth”. The distinction between this view and that of Greif and Tabellini, for example, is really quite subtle: both locate the driver of development in slow-moving social changes that predate industrialisation by centuries.

A Farewell to Alms is an entertaining and unique look at economic history, and I would recommend it to anyone seeking an economic “history of the world”. I hope that it will be read until long after the last copy of Sapiens disintegrates, forgotten. Clark was right to claim in his introduction that the book is at least “usefully wrong” (although I do think that, on balance, is what it is). What this book is not anymore, however, is nearly as contrarian as Clark believes. Sure, the particulars of his Malthusianism and Darwinianism absolutely are. But the focus on subtle, long-run cultural and behavioural changes and differences is today, for better or worse, almost pedestrian.

Supplemental: Downstream

I tried to not get too lost in the weeds of the rather empirical debate over the Malthusian model in the review. But this is the perfect place look at it a little bit more, in this case, in the context of

This comes from Humphries and Weisdorf (2018). Thanks to Anton Howes for bringing it to my attention!

For more about this, check out the supplemental to this review, which goes into Clark’s very interesting recent response in more detail.

As a mathematician and technologist who wandered into economics and technological and economic history I had some interaction with Greg in the period before _Farewell to Alms_. A grand guy and extremely smart but I never have been convinced. I've found Koyama, Mark, and Jared Rubin, _How the World Became Rich: The Historical Origins of Economic Growth_ Medford: Polity Press, 2022 to be more illuminating. I recommend it.

Brad Delong has a related current post …

https://open.substack.com/pub/braddelong/p/the-false-calm-before-steam-the-index?r=bhnq&utm_medium=ios