The City and the Mill

British Imperialism 1688-2015, P. J. Cain and A.G Hopkins, 2016 (1993).

This review is another two-parter. British Imperialism is about 800 pages long, and as with Gerald Feldman’s The Great Disorder, too large to do any justice in ~1500 words. Conveniently, it was originally published in two volumes anyway, so I do not feel bad splitting it in half. This first ‘volume’ covers the period 1688-1914, and that is what I am talking about here.

Eric Hobsbawm’s 1968 classic Industry and Empire is special to me — it is one of the books responsible for igniting my interest in economic history. It has a particular, you might say orthodox, view of Britain’s industrial-imperial arc: a rise of industry spurred by empire, until 1850, followed by imperial expansion to protect this industry once it entered a long relative decline.1 In this view, it is not simply that industry was a growing part of the British economy, quietly ushering in the modern world. It is rather a political-economic force pushing Britain to conquer and exert dominance over much of the world.

Peter Cain and Antony Hopkins, however, are not convinced industry was all that. In British Imperialism 1688-2015, the 1993 classic (republished not once, but twice since), they argue that industry was not the driver of the expansion of the British Empire. When it came to politics and empire, Cain and Hopkins suggest, industrial capitalism sat in the backseat. Instead of the highly visible tycoons of northern mills, it was the “gentlemanly capitalists” of London that were in control. To explain why the British empire grew when it did, the way it did, the authors suggest you should look south, not north.

Cain and Hopkins spend many pages defining gentlemanly capitalism, a type of sociological notion of class which involves both wealth (in agriculture and, increasingly, in financial assets) and social norms concerning political duties and respectable avenues for money-making more specific than those within concepts like “elites” or “bourgeoisie”. As they write, “not all capitalists were in the service sector or all gentlemen were capitalists”. They find inspiration in Thorstein Veblen, the 19th century economist famous for his 1899 Theory of the Leisure Class.

But you do not really need to worry about this — the nuances of gentlemanly capitalism can, I think, be safely put aside to understand British Imperialism. In the final analysis, what Cain and Hopkins are talking about is basically just the service sector: finance, communications, commerce, and transport, plus (although less significantly) the professions. This explains the 1688 start date to their periodisation— the creation of the national debt and the founding of the Bank of England are, for Cain and Hopkins, the inventions which enabled the rise of a non-industrial, non-agricultural class of capitalists.

Otherwise, British Imperialism has little to say about the 17-18th centuries. It is on the 19th century, and in particular after 1850, where the focus lies. This is when Britain is traditionally thought to have entered economic decline, as while the manufacturing output of the rest of the world rose, its agriculture was crushed by free trade. Cain and Hopkins, however, argue this ‘decline’ is much overstated. The GDP and productivity growth rate did not fall relative to other countries substantially until 1900, even if agriculture collapsed and manufacturing ‘stagnated’. Instead, services became the motor of growth. In post-1850 Britain, Cain and Hopkins say, the City of London mattered more than Manchester and its mills.

This argument is rooted in research on growth in the British economy in the 19th and early 20th century. This was a major field in quantitative economic history from the 70s, making the names of Charles Feinstein and Nick Crafts among others. Cain and Hopkins rely most on more ‘recent’ (late 80s to early 90s) research that, in particular, reappraised the role of services. Most of all, they lean on this 1990 paper by Gemmel and Wardley, “The contribution of services to British economic growth, 1856–1913”.

To sketch some of the key observations — the growth rate of commerce was on par with manufacturing from 1856-1913. The contribution to growth from transport and communication was as significant as mining. The employment share of services in Britain was greater than anywhere save the Netherlands, and London — the service hub of Britain — grew faster than any other region in the country.

Services also drove Britain’s relation with the world economy. The balance of payments deficits Britain experienced after 1870 were offset by the ‘invisible’ exports of financial services, transport, and insurance. Cain and Hopkins are convinced that technological progress in financial services, for example, was the cause of the rise of sterling as a reserve asset after 1900. This, they argue, was due to “London refin[ing] its techniques of international monetary management”, and the Bank of England proving itself as an effective lender of last resort.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Cain and Hopkins argue that services were politically far more significant than manufacturing. While industry was spread out across the country in small firms, and largely ran by men outside the social milieu of high society, those in the service sector had much closer ties both amongst themselves and to the political elite. Industry also did not get involved much in high finance. Bypassing the City, they raised funds, for the most part, via their own networks — “Britain was not one capital market but two”.2 They had less stake in the web of investment that London weaved from foreign and empire bonds, railways, and other safe securities.

This supremacy of services domestically established, Cain and Hopkins then attempt to demonstrate their key thesis: that the contours of British empire building were determined not by the atavistic demands of an aristocracy or the commercial ambitions of industry, but by this gentlemanly class of bond-owners and financiers. This, they argue, is the only explanation able to grasp the unevenness of 19th century British imperialism: why Egypt was absorbed when the Ottoman Empire was not, why South America was held at distance when Africa was occupied, and why the political grasp on the white colonies was loosened while they were economically pulled tighter.

I will not summarise all these points. Suffice to say, Cain and Hopkins have a City-centred explanation for every imperial adventure, or lack thereof. With cases where Britain kept its empire informal, the explanation is that the City had a vested interest as a creditor to foreign governments best left intact. If default was a possibility, the pressure for direct intervention was raised — as in the case of Egypt in 1888. In tropical Africa, where states were not raising many loans in London, direct rule created the best (if limited) opportunities for gentlemanly investment. In every case, industry’s wish for less spending by government and the opening of export markets came second to the City and its demand for a reliable supply of overseas lending opportunities.

Nonetheless, sometimes manufacturing interests did get their way. Cain and Hopkins generally explain this by arguing that manufacturing only won when it was basically aligned with services — when their “demands were consistent with free trade and, in general, with principles of sound finance”. This may be true, but it evidently poses an issue of causal inference. It raises how much of British Imperialism’s argument really describes industry and services mingled and aligned, rather than the dominance of services as such. The only example of manufacturing and services clashing dramatically in the book is the debate over Indian trade protection in the 1890s. Even then, manufacturing still won some concessions — hardly a clear victory on behalf of finance.

Cain and Hopkins at times make statements that aggravate this ambiguity. In discussing British policy in the Middle East, for example, they argue that “the City was [...] keen to see the unity of the Ottoman Empire upheld in order to safeguard investments there, though it, […], was sufficiently ambidextrous to back the take-over of both Cyprus and Egypt”. I cannot help wonder if this so-called ambidextrousness reflects the power of the City, or the slippery nature of Cain and Hopkins’ thesis? It is difficult to know. The adaptability of the City complicates asserting its role as a political actor.

Despite these reservations, I do find British Imperialism convincing in the key idea: that the ‘British decline’ of 1850-1914 is far from clear-cut when services and empire are taken seriously. This reappraisal might complicate hegemonic transition theories à la Braudel and Arrighi, since it is no longer clear that the decline of Britain’s preeminence was consequence of a deep process of decay. The balance of payments is perhaps not a prophet of imperial decline. It also therefore means we have to keep looking elsewhere to diagnose the causes of British decline.

In my next post I will review the second half of British Imperialism, the period from 1914 until the present. If imperial growth from 1850-1914 was determined by the global position of Britain’s service sector, then how did the Empire last so long after that sector had been dethroned, and why did it collapse when it did? Once again, it is with London, not Manchester, where Cain and Hopkins find an answer.

Paid subscribers: check out the supplemental to this review below! If you are not yet a paying subscriber and you’re curious for more, please consider signing up.

Supplemental: The City and the Mill

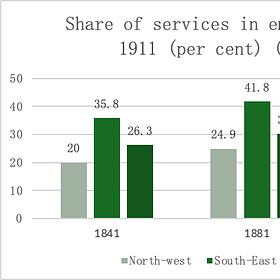

There are a lot of tables in British Imperialism but relatively few charts. So I have put a few of, to my mind, the most important tables into some quickly-formatted charts for this supplemental. All three illustrate the importance of services — the central point for Cain and Hopkins — to the late 19th century British Economy: the first in employment, the second in the balance of payments, and the third in politics.

None of this is original to Hobsbawm. That first bit, about the earlier expansion of empire, comes originally from Eric Williams. For a great explanation of the debate on this in economic history — the Williams thesis — look at

’s multi-part analysis from his (sadly, perhaps defunct) substack Great Transformations.From Davis and Huttenback’s Mammon and the Pursuit of Empire, quoted by Cain and Hopkins.

Where does greed sit in all this do you think? Is there a disconnect when it comes to the nature of wealth generation(ie growth through innovation/industrialisation vs growth through investment return - or are they inextricably and necessarily linked?)

Really appreciated this synthesis. The ‘two capital markets’ idea—one industrial, one gentlemanly—is such a sharp frame for understanding British policy contradictions.