Within and Between

The Great Global Transformation: National Market Liberalism in a Multipolar World, Branko Milanovic, 2025.

Karl Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte is surely the greatest essay ever written — at the very least, it is certainly one of the most quotable. Written and published in early 1852, right after the coup which made hitherto President Louis-Napoléon into the Emperor of France, it is essentially a piece of political opinion journalism. But Marx rises above events to produce, in the moment, a political-economic and historical analysis which has stood the test of time. The lure of recapturing this fusion of commentary and world-historic sensibility — nailing, in the first draft of history, what makes it through to the final edit — tempts many, even if precious few manage to succeed.

This is the sort of courageous task which Branko Milanovic sets for himself in The Great Global Transformation: National Market Liberalism in a Multipolar World, an unabashedly world-historical book. From the title alone, you might believe the comparison with Marx is strained. The context, content, and style of these books books substantially differ, to say the least. But I prefer to think of The Eighteenth Brumaire as a genre-defining text — a standard for writers aiming to pithily distill the essence of the political economy of their historical moment. And that is certainly Milanovic’s aim.

Milanovic’s argument is that change in the global economic order is currently being driven by two forces: the rise of China and, concomitantly, the new and emerging “plutocratic ruling elites” in China and the United States. The result is the rise and decline of “global neoliberalism”, a phrase that Milanovic has no qualms using, in favour of “national market liberalism” — that is, neoliberalism shorn of its internationalist dimension (free trade), but retaining strict market economics in the domestic sphere. So far, so lofty.

The book itself, however, can really be split into three themes. First, there is a descriptive-quantitative overview of inter-(and intra-) national inequality and wealth. Here we have Milanovic in his traditional element, where his ability to summarise comparative economic data really shines. There are, of course, the usual statistics on the rise of Asia and the decline of the West: comparisons of GDP per capita and shares of global GDP over time, charts that are so familiar by now I imagine most can visualise them in their mind’s eye.

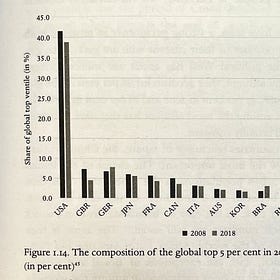

But Milanovic has an eye for unconventionally incisive statistics as well. There is, for example, a table of the year each country reached peak income, relative to global income (the US is 1952; the UK 2004; most of Asia, of course, is now). Another is the changing composition of the global top 5% of earners, a group still dominated by the US. From 2008 to 2018, however, Chinese high-earners in this group increased five-fold to 5%: more than one in twenty high earners globally today are Chinese. Milanovic estimates that if we have a ‘growth gap’ of 3% per year between China and the US for another twenty years, then the shares of Americans and Chinese in the top global decile will be equal.

Milanovic is at pains not to overstate the ‘positional decline’ of the West. Still, an overwhelming share of global wealth resides within it. But trends like that above are apparent, and have social consequences. The relative decline of the lowest deciles in the West makes for another example. The least well-off have seen their relative position decline most. The lowest decile of Germans sat at the 81st percentile globally in 1993, but fell to 73rd in 2018. This matters more than you might think, Milanovic argues. As he writes:

…while in the past both a German worker and a German engineer were able to afford a vacation in Thailand (a global good), in the future only the latter may be able to do so. Or to buy the newest type of smartphone or attend the football World Cup.1

Perhaps Milanovic’s sharpest quantitative insight is on the intranational level: his identification of ‘homoploutia’. This neologism of his refers to the growing tendency for elites to be both high earners of capital and labour income. This is measured by Milanovic as the share of people who in the top income decile who are also in the top decile of labour and capital income. In the US, at least, the share of homoploutic elites has risen from 20% to 30% since 1975. This is, Milanovic declares, “arguably the only development in modern capitalism that would surprise Marx”.

Homoploutia matters for Milanovic because it is, in his opinion, the source of a transformation in the makeup of elites in the West over recent decades. His view is that it explains how, despite what 20th century thinkers like Burnham, Galbraith, and Schumpeter thought, the rise of the so-called managerial class was not antagonistic to capitalism but symbiotic with it. Milanovic dips in and out of the more ‘cultural-sociological’ side of things, noting the connection of homoploutia to “credentialism”, while wisely avoiding these politically-fraught waters for the most part. But what his analysis lacks is much comment on the future of homoploutia. Will the share of homoploutic elites keep rising? If not, what forces may stem it? In either case, what might the consequences be? These are not questions Milanovic attempts to answer.

Milanovic’s book is not only concerned with deciles. As anyone who picked up his excellent Visions of Inequality is well aware, Milanovic also moonlights as a historian of economic thought, and much of The Great Global Transformation is intellectual history. Milanovic’s primary interest here is the ‘doux commerce debate’ — the age-old question of whether international trade begets war or peace. His survey includes the usual figures: Montesquieu and Smith, Hobson and Lenin. But the main focus is on Schumpeter, who Milanovic argues had a theory of imperialism that is “exceedingly close” to the Marxist trade-brings-war theory of inter-imperialist competition.

This Schumpeterian view of trade, as Milanovic describes it, suggests that the capitalist economy has two modes: a free-trading one, where commerce really is doux, and a mercantilistic, monopolistic mode where trade becomes a zone of violent competition. This is clearly Milanovic’s own view. In his opinion, the model describes well the history of Sino-American relations from 1970 to the present, and, on a basic level, I doubt many would disagree with this. But how useful this model is not clear. Milanovic claims the pattern is cyclical, but the mechanisms which produce this cyclicality are left opaque. If we now inhabit the monopolistic mode as Milanovic suggests, under what circumstances will this last? What might push in the other direction? Again, these are questions which Milanovic leaves largely unanswered.

For a relatively short book, Milanovic covers a great deal of terrain. Although I have not discussed it here — mainly because I do not feel informed enough to comment — there is much material on the political economy of China, which includes the makeup of China’s elites, the ideology of Chinese leadership, and how this all may, or may not, change post-Xi Jinping, among other things. The European Union, on the other hand, is mentioned only a handful of times. It is not an omission you notice much.

As the unsubtle allusion in the title reveals, one of Milanovic’s inspirations is Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation, one of the first books I reviewed on this blog. I understand the comparison. Polanyi’s book, while it drew a wide-ranging (if empirically questionable) historical picture, was largely motivated by its author’s present: the issue of explaining fascism. Clearly, Milanovic has a similar goal in mind: tracing the contours of 21st century development, but with an eye to explaining the ‘new cold war’.

However, Milanovic’s book actually reminds me most of Giovanni Arrighi, and in particular, his 2007 Adam Smith in Beijing. The resemblance is striking. For starters, both writers are partial towards displaying qualitative information in tables, diagrams and flow-charts (For an example, Milanovic’s book features a chart indicating personal relationships of prominent politicians in the US and China). More seriously, though, Milanovic and Arrighi are both trying to write their own Eighteenth Brumaire — connecting current events (in Arrighi’s case, the Iraq War and Chinese development; in Milanovic’s, contemporary Sino-American tensions) to an analysis that, the authors hope, at least, draws out the truly historical socio-economic trends beneath.

But The Great Global Transformation lacks one thing Arrighi never shied away from: predictions. Arrighi’s model of capitalist development came with many of these (despite some gripes with Adam Smith in Beijing I have to admit that these could be rather prescient — I am reminded often of Arrighi’s well-aged prediction that a declining US will seek to extort its allies).

But with Milanovic, you only detect the conviction that a historical period has ended, and another has taken its place: the era of global neoliberalism is over, and the era of “national market liberalism” has begun. This is a conviction that Milanovic defends masterfully, with a remarkable breadth of quantitative and qualitative evidence. But his thesis ends there. Like Polanyi, Arrighi and Marx, Milanovic takes an imperfect-if-admirable shot at grasping the origins of our present moment. But unlike them, he steps back from asking: where next?

Supplemental: Within and Between

There are many charts and tables in The Great Global Transformation. Here is a selection of some that I mentioned in my review, and some which I did not.

You can’t fault Milanovic for insufficient prescience here, given recent furore…

Really great review (as usual). Ironically I found the ‘National Market Liberalism’ bits of the book the least convincing. The first sections as you say are where Milanovic is most comfortable, and where he shines. But I’m not sure the National Market Liberalism thesis fits in the three cases he lists (US, China, Russia) as well as he is arguing, and for an overarching theory there seem to be too many exceptions. Still - a good *thesis* is valuable, even to critique!